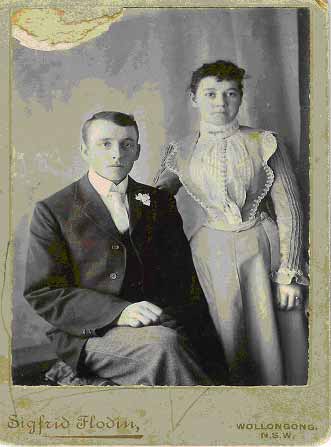

Thursday 31st July 1902. George Bertram Adams (my great grandfather) 23 years of age, finished breakfast around 5.30am. Then strapping on his miners belt, with tucker tin attached, kissed Jane, his wife of 8 months, (18 years old and pregnant with my grandmother) goodbye. He clumped down the wooden steps at the front of his company owned miners cottage, in Soldiers Road Kembla Heights; walked the half mile up the road to Mount Kembla Mine and stepped into history. (above George and Jane Adams (nee Paterson) wedding photo 27 November 1901).

At 2.03 pm that day the mine exploded; propelling the tiny village onto the national and world stage. By days end 96 men and boys were dead. More were to die of the effects later, taking the unofficial toll over 100. The number of people whose lives were devastated and forever altered was uncountable; the depth of their grief unfathomable. Reverberations of the explosion echoed around the world. Messages of support and some aid were received from America, Russia, Europe and the old country, Great Britain. Closer to home the blast was heard (halting proceedings) at an arbitration hearing into mine safety in Wollongong, some 8 miles away. Many headed to Mt Kembla to help. Others had more sinister intentions for, in the absence of their occupants, every house in Mt Kembla was looted.

While all this was being enacted, my great grandmother ran to the mine. I cannot begin to imagine her anguish. Some pregnant women miscarried with shock. If this had happened to my great grandmother I would not be telling this story to you now.

While she agonised at the pit top her husband of 8 months was sitting against a pit prop miles underground beneath her scratching a farewell note to his young wife, with a nail onto the tucker tin he had strapped on that morning. He had felt the early effects of the afterdamp and was preparing to die. Fortunately for our family, and many others, the Day Deputy, David Evans, was able to gather some 70 men together and lead most of them, including my great grandfather, out of the mine by the old, abandoned, long wall workings. They crawled through collapsed goafs and narrow passages that were only used, at that stage, for ventilation. Eventually emerging at what was called the Managers Day Adit well to the South of the main entrance. He was out alive!

I have no knowledge of the emotion of their reunion or the words scratched on the tucker tin. The disaster was rarely spoken of in our family.

The unfortunate epic of the bungled relief effort is a sorry tale in itself and deserving of a full story of its own. Suffice to say that a combination of greed, neglect and mistakes led to Mount Kembla’ s 33 widows and the 120 fatherless children (only counting those under the age of 14 years) being largely dependant for their existence on those in the village who were more fortunate. This led to great internal social pressure, which no small community should have been allowed to bear alone. Not surprisingly, with stoic resolution, the community turned inward. Looking after its own and treating with hostile suspicion any interference (positive or negative) from outsiders.

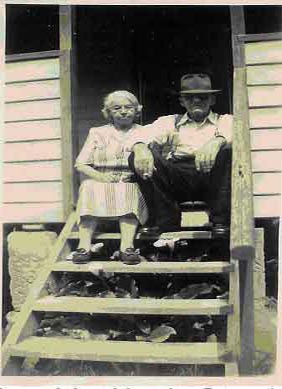

This stoic resolution was evident to me some 50 years later as I sat on the wooden steps in front of the same company owned miners cottage my great grandfather had left for work from on that fateful day. Both he and my great grandmother were alive for the first decade of my life. I remember him being a warm and humorous man, not averse to spinning a yarn, on almost any subject, without letting the truth interfere with a good story. However I remember the unnerving feeling of coolness if I blundered onto the subject of the disaster. The still raw wounds from the neglect and abandonment of people in need would lead to a vitriolic comment about the ‘Bastards’ and stifle any further discussion on the subject. The suspicious hostility is evident in the community to this day. Although the exact reason for the suspicion would not be understood by the perpetrators or the victims of it. It has seeped down the years as insidious as the afterdamp that was partly responsible for it.

This disaster is the greatest loss of life in an industrial accident in Australia’s history. It is the greatest loss of life in any single event on the mainland in peacetime in Australia’ s European history. Yet tragically this event of outstanding historical significance has been let slip from public awareness.

As the small communities of Mt Kembla and Kembla Heights had shown in the dark years immediately after the disaster, the resilience of the human spirit is indomitable. So, not surprisingly, this resilient spirit shone through a son of one of the survivors. The singular efforts of Fred Kirkwood stand like a beacon to those who must now preserve and foster the heritage he has entrusted to us. Fred Kirkwood, church warden, oral historian, guardian of memories, inspirer of a new generation, son of a workmate of my great grandfather; almost single-handedly kept the focus on the remembrance of the disaster by organising, in the Mt Kembla Soldiers & Miners Memorial Church, an annual service to be held on its anniversary (31st July) from the 1930s to the year of his death at 93 years of age in 2003. His body now lies in his beloved churchyard of the Mt Kembla Soldiers & Miners Memorial Church but his spirit is alive and well, residing in the Mt Kembla community and the people he has inspired.

After tenaciously guarding the memory for so many years it was almost beyond his power to let go. However, as if scripted by an omniscient author he gave his blessing to Cate Stevenson, who was the driving force behind the Mt Kembla Disaster Committee, to go ahead and take up the baton. Perhaps realising he could not go on he saw a new generation of Mt Kembla people was the only way to perpetuate the memory in living history, and not consign it to the musty shelves of library archives.

Fred’ s reluctance to leave the memory of such a nationally significant event to the history books is well justified. Despite the enthusiastic and articulate literary efforts by many people in response to the disaster:- (Stuart Piggin & Henry Lee, with their definitive work ‘ The Mt Kembla Disaster’ [Oxford university press 1992] now out of print; as is the play ‘ Windy Gully’ [Currency Press 1989] by inspired playwright and Mt Kembla resident Wendy Richardson; Poetry form Cordeaux Bushman, Historian and Poet J.L. [Jack] McNamara, such as his masterful ‘Of Kembla Colliery’ as well as; Conal Fitzpatrick’s chillingly evocative ‘Kembla the Book of Voices’ ) all being received enthusiastically by the local and niche markets, the subject has not yet risen on the horizon of the wider public’s consciousness. As Fred Kirkwood rests after his earthly toil, the memory of the disaster has but a tenuous grip on the historic psyche of NSW and Australia. It relies heavily on the small but enthusiastic group of new generation Mt Kembla people.

Mickey Brennan, a young wheeler in the Mt Kembla Mine on the 31st July 1902, has the dubious distinction of being the only body never recovered from the disaster. His father is said to have had a coffin waiting in the machine shed while he searched every recess of the mine for two years. After which he walked into the Ocean in Wollongong. Some say committing suicide.

Folklore tells of Mickey Brennan’s ghost haunting the mine, making strange noises, up until its closure in 1970. After this several publicans of the Mt Kembla Hotel report having seen or heard Mickey’s ghost in the cellar of the hotel. Hopefully the story of the disaster will not suffer the same fate as that of Mickey Brennan’ s ghost; Unrequited, searching for recognition and proper acknowledgement in the annals of Australian history.

Perhaps there is a need for my great grandparents, Jane and George Adams, to sit on the wooden steps of the old miner’s cottage in Kembla Heights and spin us a yarn about how it was.

Perhaps they just have.

George and Jane Adams (nee Paterson) October 1951 just short of their golden anniversary 27 November 1951. (Taken on the front steps of their Soldiers Rd (now Harry Graham Dr) Kembla Heights)

(c) Phillip Donaldson, Deputy Chairperson, Mt Kembla Mining Heritage Inc.

Web: www.mtkembla.org.au